Wisdom Beyond Knowledge: Lessons from Good Will Hunting

The acquisition of knowledge requires voluminous reading, steady listening, and earnest learning. Wisdom, on the other hand, requires all of this and much more.

Where is the wisdom we have lost in knowledge?

Where is the knowledge we have lost in information?

—T.S. Eliot, Choruses from “The Rock”

“You like apples?” Will asked through the bar’s plate glass window with a sardonic smile on his face.

“Yeah,” answered the sheepish, pony-tailed, oxford-and-sweatered Harvard student.

“Well, I got her number,” smashing the napkin with a girl’s name and number against the window. “How do you like them apples?”

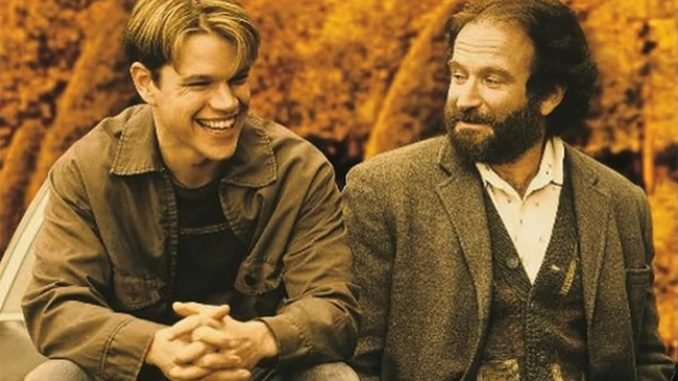

Anyone who had a pulse during the 1990s remembers when Will Hunting (played by Matt Damon), a troubled savant from Southie, verbally slapped the cocky Harvard student with this immortalized line. As the story in Good Will Hunting goes, the Harvard student pulled intellectual and class rank on Hunting’s poor friend Chuckie Sullivan (played by Ben Affleck) as Chuckie flirted with a Harvard co-ed. The obnoxious student peppered Chuckie with questions out of his Harvard history and political science books for wicked sport. That’s when Will Hunting defended his friend revealing how the Harvard student was a fraud lifting passages from books for the sake of sounding smart—books, incidentally, that Hunting had read and remembered more keenly and to greater effect than the student. The scene culminating in “How do you like them apples?” was something deliciously worthy of Clint Eastwood in a Dirty Harry movie.

We are so impressed with knowledge. Legitimately or not, the Harvard student—merely because he was accepted to Harvard and, presumably, thriving—inspires a certain admiration for his intellectual wattage. Simultaneously, Will Hunting’s cool knowledge—a mastery of facts acquired from relentless reading—engenders awe. His facility with raw information in rebutting this bully is something to behold. But if we watch Good Will Hunting in its entirety, we soon realize that knowledge isn’t all.

Sean Maguire (played by Robin Williams), a seemingly washed-up community college professor of psychology, is charged with corralling the young and unbridled Will before he self-destructs. Perspicacious and fundamentally invested, Sean sees through Will’s complex defense mechanisms. Will uses his knowledge—his genius—to attack others and shield himself from pain. After Will lashes out at Sean, they meet on a park bench the next day. Sean calmly, but emphatically upbraids Will for his shallowness, his love of knowledge at the expense of wisdom.

If I asked you about art, you’d probably give me the skinny on every art book ever written. . .Michelangelo? You know a lot about him. Life’s work, political aspirations, him and the Pope, sexual orientation, the whole works, right? But you can’t tell me what it smells like in the Sistine Chapel. You’ve never actually stood there and looked up at that beautiful ceiling. I’ve seen that. If I asked you about women, you’d probably give me a syllabus of your personal favorites. . . .But you can’t tell me what it feels like to wake up next to a woman and feel truly happy. You’re a tough kid. If I asked you about war, you’d probably throw Shakespeare at me, right? “Once more into the breach, dear friends.” But you’ve never been near one. You’ve never held your best friend’s head in your lap and watched him gasp his last breath, looking to you for help. If I asked you about love you’d probably quote me a sonnet, but you’ve never looked at a woman and been totally vulnerable. Known someone who could level you with her eyes. Feeling like God put an angel on earth just for you, who could rescue you from the depths of hell. And you wouldn’t know what it’s like to be her angel. To have that love for her be there forever. Through anything, through cancer. You wouldn’t know about sleeping sitting up in a hospital room for two months holding her hand, because the doctors could see in your eyes that the terms visiting hours don’t apply to you. You don’t know about real loss, because that only occurs when you love something more than you love yourself. I doubt you’ve ever dared to love anybody that much. I look at you and I don’t see an intelligent, confident man: I see a cocky, [scared] kid. But you’re a genius, Will; no one denies that. No one could possibly understand the depths of you. But you presume to know everything about me because you saw a painting of mine. You ripped my [—] life apart. You’re an orphan, right? Do you think I know the first thing about how hard your life has been, how you feel, who you are, because I read Oliver Twist? Does that encapsulate you? Personally, I don’t give a [—] about all that, because you know what? I can’t learn anything from you I can’t read in some [—] book. Unless you wanna talk about you, who you are. Then I’m fascinated. I’m in. But you don’t wanna do that, do you, sport? You’re terrified about what you might say. Your move, Chief.

Will is knowledgeable. But Sean is wise.

Compared to wisdom, knowledge is easy. To be sure, the acquisition of knowledge requires voluminous reading, steady listening, and earnest learning. Wisdom, on the other hand, requires all of this and much more. Wisdom requires patience and humility, discernment and decision, feeling and growing, experiencing and navigating. It requires putting knowledge into action—action that has real-life consequences beyond a grade on a paper or the buzz of affirmation. It isn’t simply dropping a fact as in a game of Jeopardy or Trivial Pursuit. It involves living by right reason and enduring the consequences of such a life. Luke Skywalker, Harry Potter, and Bilbo Baggins all chafed against the tempering tutelage of their wiser mentors. “I know! I know!,” they insist. “Yes. I know you know,” Obi-wan, Dumbledore, and Gandalf answer their apprentices, “but you don’t yet understand.” You are smart, but not wise.

In a 2003 interview, Joseph Epstein told a story that illustrates the difference between knowledge and wisdom,

I have a cousin who died recently. A guy named Sherwin Rosen, who I loved, really. He was the chairman of the Economics Department at Chicago and at a memorial dinner for him this man Gary Becker who won a Nobel Prize in Economics said, “You know when Sherwin was a graduate student here we almost canned him because he was slow in response. If you asked Sherwin a question, he would say, ‘Gee, I am not certain,’ and then he would come back a month later. He brooded on these things. But he saw aspects in the question none of us did. Becker said being fast in response is one of the things we look for in good students. But it’s a mistake.”

Wisdom is humble enough to know that knowledge is not enough. Knowledge is an ingredient of wisdom—necessary, but not sufficient. As Rainer Maria Rilke once advised a young, inexperienced poet, “Do not now seek the answers, which cannot be given you because you would not be able to live them. And the point is, to live everything. Live the questions now. Perhaps you will then gradually, without noticing it, live along some distant day into the answer.” Robert Caro, the famed biographer of Robert Moses and Lyndon B. Johnson, declared, “Truth takes time.” Put another way, wisdom is knowledge that pauses, prays, and looks both ways before walking on.

To be sure, Will Hunting is a fascinating figure—a genius. But Good Will Hunting is not a story of a genius; it is the story of a genius finding his way to wisdom with the help of a mentor. Wisdom beyond knowledge.

Now that’s a tale worth telling.