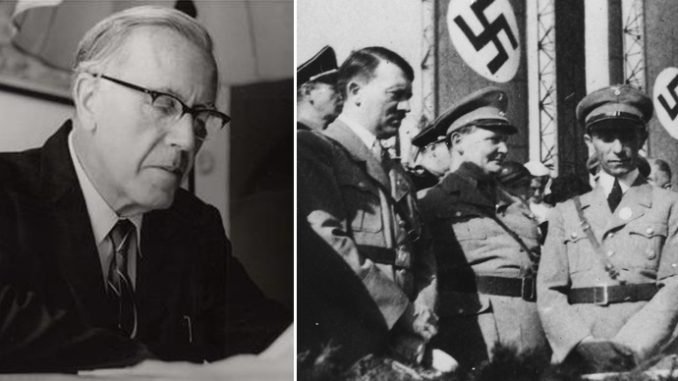

The Conductor: Lessons from Dietrich von Hildebrand’s battle against Hitler

The great philosopher was courageous and brilliant. But his greatest strength was his uncanny apprehension of the truth.

“Do you know that God has granted you a rare sensus supernaturalis (sense for the supernatural)? And do you realize clearly the responsibility that such a gift entails?”—Fr. Gustave Desbuquois to Dietrich von Hildebrand

“That damned Hildebrand is the greatest obstacle for National Socialism in Austria. No one causes more harm.”—Franz von Papen, Nazi Ambassador to Austria

It was pretty early when the Nazis recognized the threat posed by Dietrich von Hildebrand. Founded in 1919 by Anton Drexler, the German Workers’ Party was a militant nationalist response to the German surrender in the First World War, the ensuing Versailles Peace Treaty, and the pockets of revolutionary violence springing up throughout Germany. Later that year, a young, fiery German named Adolf Hitler would take the movement by storm with his rapier tongue and blistering rhetoric. By 1920, the party was re-branded the National Socialist German Worker’s Party and soon dubbed the Nazis.

Meanwhile, Dietrich von Hildebrand, a young Catholic convert and adjunct professor of philosophy at the University of Munich, spoke out at a 1921 post-war peace conference in Paris. Hildebrand had no reservations about publicly calling the German wartime invasion of neutral Belgium “an atrocious crime.” To openly declare this while Germany boiled in a cauldron of blood-and-soil nationalism and ideological radicalism, was to open himself to vitriol and death threats. The German Workers’ Party took special note of Hildebrand’s courage, principles, and perspectives and declared him an enemy. At the time of Hitler’s failed attempt to overthrow the German government in the 1923 Beer Hall Putsch, Hildebrand’s name was already on the Nazi blacklist and marked for death.

But this didn’t sway Dietrich von Hildebrand.

In reading Hildebrand’s memoirs (translated and edited by John F. and John Henry Crosby), My Battle Against Hitler: Faith, Truth, and Defiance in the Shadow of the Third Reich, I discovered just why Hildebrand would be declared “enemy number one” by Hitler’s henchmen.

To be sure, Dietrich von Hildebrand was courageous. Like many dissidents or martyrs of the twentieth century (consider Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Vaclav Havel, Leszek Kolakowski, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Fr. Maximilian Kolbe), Hildebrand was fully committed. He scrupulously analyzed the Nazi ideological program, unflinchingly articulated myriad rebuttals, and fearlessly crusaded against the rising radical tide. Even though Hildebrand loved his job, his home, his country and his proximity to colleagues and friends, he nevertheless sacrificed everything to stand by the truth. In a position to obfuscate, he openly declared the Jewish status of his grandmother, which led to his removal from his professorship.

With gifts of great intelligence and eloquence to capably ingratiate himself to the Nazis, hedge on the truth, or keep quiet for personal advantage, he refused any such safe harbors unfailingly following his well-formed conscience. And having family and friends across Europe with whom he could easily have tucked himself away from danger and quietly minded his own business, he never countenanced such an abdication of responsibility. With the Nazis (as with any godless ideology), there could be no modus vivendi. Dietrich von Hildebrand stood for something and, in so doing, gave up everything.

What is even more impressive about Dietrich von Hildebrand, however, is his uncanny apprehension of the truth. Rooted in Scripture and the Sacraments, versed in the phenomenology and personalist philosophy, Hildebrand’s moral foundations were unshakeable. And this understanding gave him great comfort in his mission. “I had the consciousness that what I was doing was right before God,” he recalled, “and this gave me such inner freedom that I was not afraid.” In being well-formed, Hildebrand recognized the dangers of collectivism, where the God-given dignity of the individual is subsumed by the mood and caprice of the mob (and its inevitably self-appointed, power-hungry masters). He criticized the philosophy of reductionism and materialism that rationalized away morality and rendered consciousness a clunky matter of brain chemistry. He sensed the paradox of inhumane policies clothed in disingenuous humane language.

Finally, Hildebrand was blessed with a keen sense of human nature and the tendency (among family, friends, colleagues, and even himself) to fall prey to sloppy thinking. People, Hildebrand recognized, can become lazy in their understanding of truth and fearful about threats to their loved ones and themselves. It is natural. As such, Hildebrand saw friends rationalize and professors compromise, priests hedge and bishops obfuscate. Knowing that the Nazis cynically traded in half-truths and false assurances, Hildebrand’s good natured and fearful associates were easy to manipulate. And while Hildebrand was no scold, he called everyone to supreme alertness. One student recalled,

Heidegger’s melodies no longer had the power to seduce us, for our ears had become more discerning. Whoever understood von Hildebrand was saved. Despite many factors at work, I think one can rightly say that history might have been quite different had there been more professors like him.

In a way, Hildebrand considered this his greatest work:

The discernment of spirits, which alone mattered in that moment, simply required one to ask whether a person clearly grasped the nature of National Socialism and whether they rejected it completely on the basis of the right philosophical and moral reasons. Where this was the case, differences of opinion could be postponed for a later time.

To know the truth, yes. To stand up for the truth, for sure. But Hildebrand’s charge to alert others (even if, at times, serving as a Cassandra) that the deceptively soothing, but nefarious temptation to be agreeable with evil will end not in deliverance, but in perdition. Hildebrand reflected,

[I had to] shed new light, on the absolute impossibility of any kind of compromise with National Socialism. For it is unbelievable how vulnerable our human nature is to falling into illusions and to growing numb in our indignation over injustice which we come to accept. Here, as in so many others in life, we must be like the conductor of an orchestra, in continually renewing the call to alertness. The moment one lets up, people fall asleep, or at least become indifferent.

Beyond odd pockets in dark corners, National Socialism has been destroyed. But ideology has not. Nor has the human tendency to fool ourselves. When it comes to knowing (and embracing) the truth, having the courage to defend it, and the wisdom to sense our propensity to betray it, it would be difficult to find a better conductor than Dietrich von Hildebrand.